Here's what Halevy Street looks like today:

Here's a summary I found online:

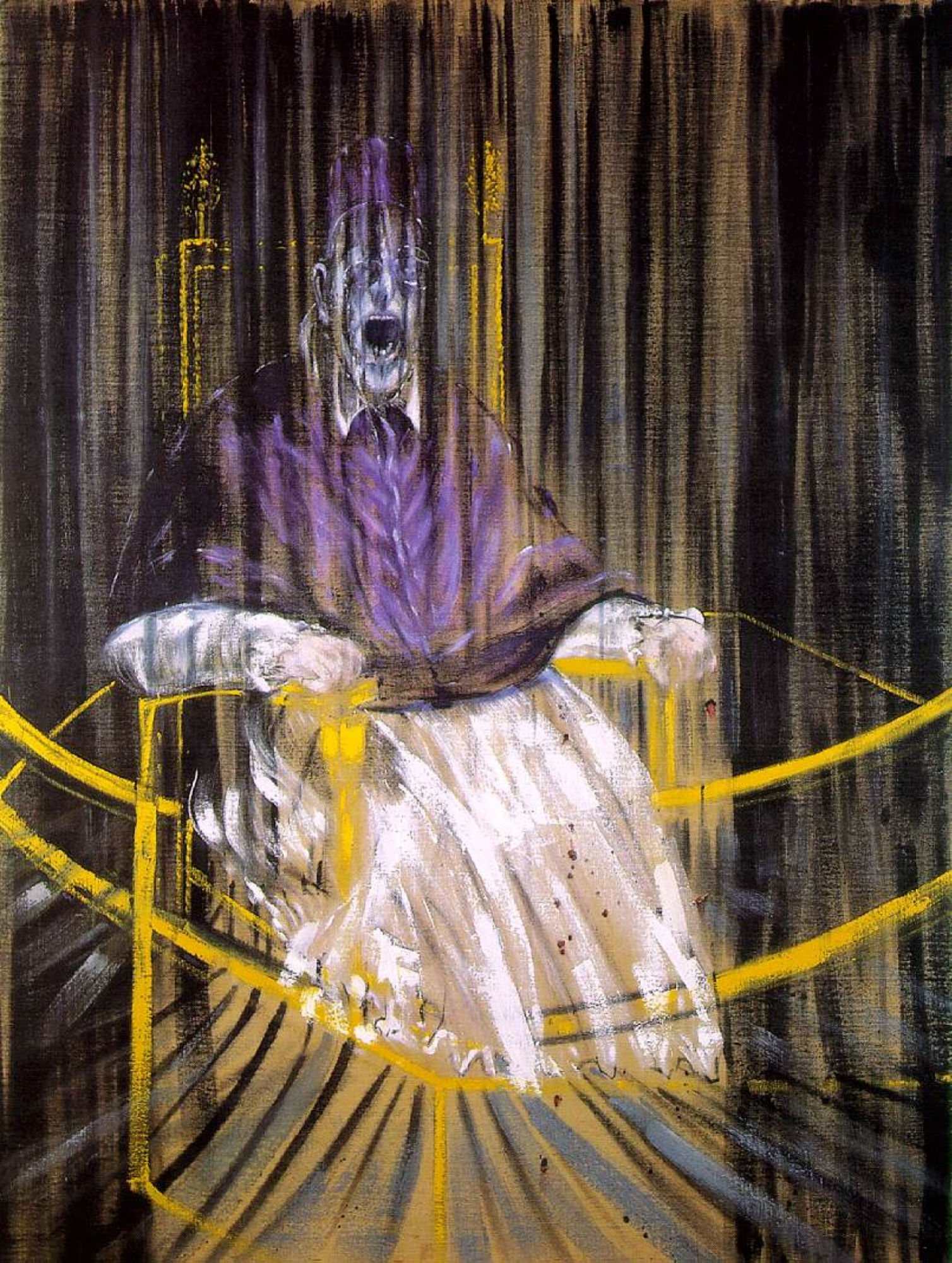

Caillebotte’s La Rue Halévy, vue du sixième étage is the embodiment of the new Paris that emerged in the middle of the nineteenth century. Inextricably linked to the moment it depicts, the present work contains a profound originality that demonstrates Caillebotte’s development of novel modes of representation commensurate with the experience of modern life in nineteenth-century France. As one of the most remarkable in the series of his urban landscapes La Rue Halévy, vue du sixième étage exemplifies the innovative pictorial inventions for which Caillebotte was celebrated. Caillebotte made his debut with the Impressionist group during their second organized exhibition in 1876. The works he chose to exhibit were praised for their ingenuity and their creator lauded. Critic Marius Chaumelin exclaimed: “Who knows Mr. Caillebotte? Where does Mr. Caillebotte come from? At what school did Mr. Caillebotte receive his training? Nobody could tell me…” He went on to say, “All I know is that Mr. Caillebotte is one of the most original painters to be revealed in several years, and I am not afraid of compromising myself by predicting that he will be famous before long. In his Floor Scrapers, Mr. Caillebotte proves to be a realist just as crude but more witty than Courbet, as violent but more precise than Manet…. If intransigence meant painting this way, I would advise our young school to become intransigent” (quoted in Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye (exhibition catalogue), op. cit., p. 100). Caillebotte would go on to exhibit with the Impressionist group in the majority of their subsequent exhibitions including the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition in 1879 where Caillebotte submitted La Rue Halévy, vue du sixième étage.

From 1875 until 1882 Caillebotte made several paintings that thematized novel vantage points, exploring the confrontation between interior and exterior spaces in the new city (see figs. 1 & 2). Caillebotte’s scenes of urban realism would become his hallmark and these paintings were a testament to the transformation of the city of Paris in the middle of the nineteenth century. As part of the ambitious reforms Napoleon III introduced during the 1860s, Georges-Eugène Haussmann was charged with masterminding a radical reconfiguration of Paris. Many parts of the medieval city were razed to provide space for an extensive grid of straight roads, avenues and boulevards (see fig. 3). The "Haussmannisation" of Paris, which is celebrated today as the precursor to modern urban planning, set the tempo for modern life. Haussmann’s expansive boulevards were the landscape of Parisian modernity and the setting of the ever-changing, ephemeral moments which formed the essence of the renovated city. Whereas the pre-Haussmannian, essentially Medieval Paris was made up of buildings that held interior courtyards, the modern apartment buildings that characterized the architecture of the new city had grand balconies and large windows that faced toward the street, offering startling new views of the boulevards below. Impressionist painters Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet frequently chose views of the French capital that captured the grandeur and commotion of the modern city (see fig. 4). Caillebotte explored this theme as well, painting in the midst of the bustling streets and in innovative compositions from an elevated vantage point above.

In La Rue Halévy, vue du sixième étage the artist has adopted a viewpoint well above the lively city boulevards below. The plunging perspective is heightened by the embrasure of window visible along the left edge which further enhances the sense of a place, a window on the upper floors overlooking the urban environment. From his elevated vantage point Caillebotte is afforded the freedom to view and manipulate perspective, tilting the ground of the picture plane in a manner that has been considered characteristic of his work and one of his greatest contributions in the move towards Modernism. Much like his vision of life in modern Paris, Caillebotte’s style combines new and old in a thoroughly contemporary manner; he retained a clarity in his draftsmanship that is related more to the French realist tradition, and yet uses radical compositional and perspectival devices that are entirely avant-garde.

The first owner of La Rue Halévy, vue du sixième étage was Caillebotte’s life-long friend, Paul Hugot. Hugot was an early supporter of Caillebotte and owned the largest collection of his work outside the Caillebotte family, including a life-size portrait the artist painted of Hugot in 1878. La Rue Halévy, vue du sixième étage was later in the notable collection of prominent New York industrialist Chester Roth. The present work has been included in major retrospective exhibitions of Caillebotte’s work and in numerous publications as a supreme example of the artist’s pioneering urban naturalism.

Data analyst here. It really do be like that. You can use stats to prove anything.

Yfw they say data doesn't lie. Looool