I think I'm ready to start getting Owl of the Year underway!

Last year went well, but between you guys' feedback and my own, this year will be mostly the same, but a few improvements.

First change is the competitors. Last year I picked every owl, but this year I'll let you choose! I'm hoping that makes a few early rounds more exciting, since they will all be the owls you want to see.

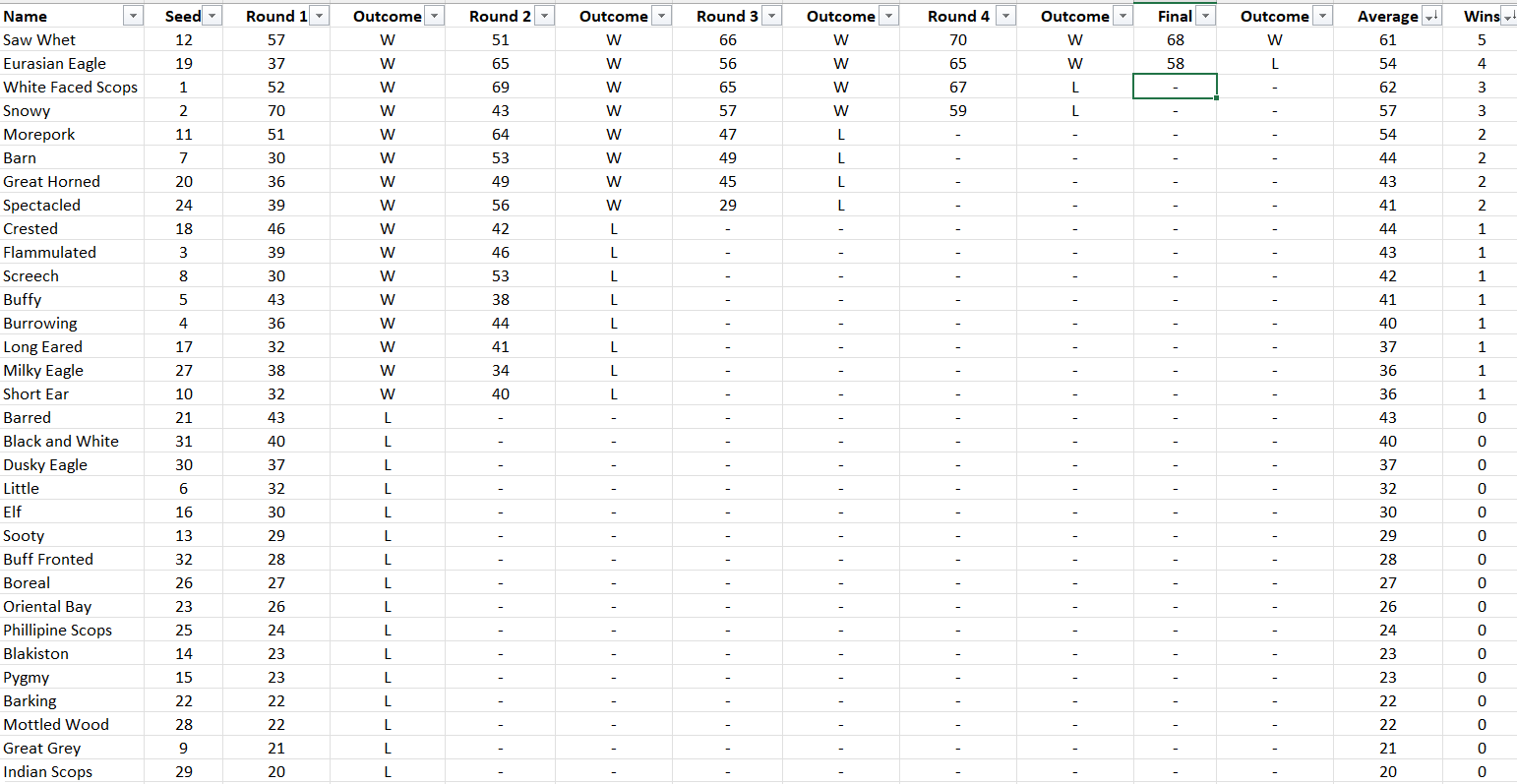

I'm keeping everyone who moved onto the second round in. These owls are:

- Barn

- Buffy Fish

- Morepork

- Little

- Snowy

- Short Eared

- Great Gray

- Flammulated

- Burrowing

- Elf

- Saw Whet

- White Faced Scops

- Sooty

- Blakiston Fish

- Northern Pygmy

- Eastern Screech

Everyone who got knocked out has to compete to stay in. Those will be competing here. I'll let this run for the week so everyone has time to vote.

I'll put the 16 from last year in this post, and next week I'll run 16 newcomers! Top 8 from each will go on to the tournament to face the 16 returning owls.

Rules are simple and the same as before: simply upvote which you like.

Vote for one or two, vote for all, vote for none, the choice is yours.

Downvotes do not count.

In the need of a tiebreaker, I defer to my SO's vote, so I have no way in much of anything as far as results go.

Second change, the prize. Last year, this was all pretty new, and it was originally going to be a purely symbolic prize, other than we changed the banner and icon to reflect the finalists and winner.

It ended up being very fun, and in the spirit of owl celebration, I made a cash contribution in c/Superbowl's name to my local owl rescue. I did this mainly because I was familiar with them and knew they were legit.

Now that we've been doing this for over a year and have seen over a hundred rescues I'm sure, I thought if you guys had any rescue story that has stuck out this year or if there's a name you feel you have seen a lot like (in no particular order) A Place Called Hope, Middle TN Raptor Center, the University of MN, The Raptor Trust, or anyone else, give them a shout out during any of these threads or message me, and I can have you guys vote who gets the prize this year.

I do not want any money from you, and I will never ask for it. If you like the work you see here, donate directly to the rescue or get them something from their wishlist. I'm still going to donate this year again to my local rehab because it made me happy. This prize will be in addition.

With all that out of the way, here are your first contests!

#superbowl #owloftheyear24