The first Philadelphia Maker Faire was extremely impressive, and seemed poised to be one of the premier maker events on the East Coast. Unfortunately, it had the misfortune of happening just a few months before COVID-19 made such events impossible. Robbed of all its momentum, the event tried out different venues after the shadow of the pandemic was gone, but struggled to meet the high bar set by that inaugural outing.

But after attending the the 2025 Philadelphia Maker Faire this past weekend, I can confidently say the organizers have moved the needle forward. This year marks the second time the event has been held at the Cherry Street Pier, a mixed-use public space with an artistic bent that not only lends itself perfectly to the spirit of Maker Faire but offers room for expansion in the future. The pier was packed with fascinating exhibits and excited attendees, and when the dust settled, everyone I spoke to was thrilled with how the day went and felt extremely positive about the future of the Faire.

But after attending the the 2025 Philadelphia Maker Faire this past weekend, I can confidently say the organizers have moved the needle forward. This year marks the second time the event has been held at the Cherry Street Pier, a mixed-use public space with an artistic bent that not only lends itself perfectly to the spirit of Maker Faire but offers room for expansion in the future. The pier was packed with fascinating exhibits and excited attendees, and when the dust settled, everyone I spoke to was thrilled with how the day went and felt extremely positive about the future of the Faire.

Providing coverage of an event like this is always difficult, as there’s simply no way I could adequately describe everything there was to see and do. The following represents just a few of the projects that caught my eye; to see all that the Philadelphia Maker Faire has to offer, I’d strongly suggest you make the trip out in 2026.

Wasteworld Toys

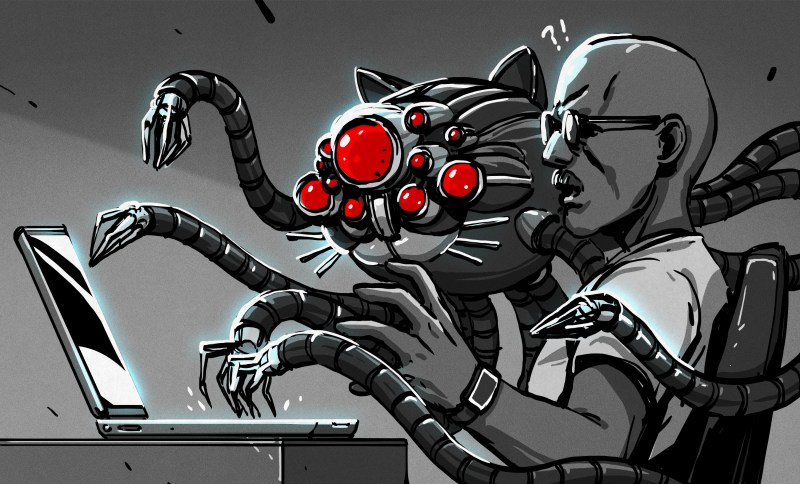

Of all the awesome projects I saw during the Faire, the one that stuck with me the most has to be Brett Houser’s Wasteworld Toys. This incredible collection of hand-made remote controlled vehicles invoke the look and feel of the Mad Max universe, but are populated with its own cast of post-apocalyptic characters that come from the depths of Brett’s obviously considerable imagination.

Whether your saw them as pieces of art or electronic marvels, it was impossible not to be impressed with the work Brett put into these builds. While there were some 3D printed parts and cannibalized model kits, much of the raw material used to build the vehicles and characters came from the trash. Brett has an eye for repurposing everyday objects, like taking the metal top from a disposable lighter and turning it into an armored faceplate for one of his Wasteworld warriors.

Beyond being able to simply drive them around, most of the vehicles had some secondary function. One was equipped with an Airsoft cannon, another had a functional flame-thrower, and there was even a mobile rocket launcher that actually fired tiny rockets. They weren’t all weapons of war though: there was a surveillance van that featured a tiny display showing nearby WiFi networks, and a tricked-out station wagon that had an emulated version of Contra running in the back that you could play with a Bluetooth PlayStation controller.

Many of the vehicles featured first person view (FPV) capabilities, with the cameras so expertly hidden on the vehicles and cybernetic characters that at first glance you assume they’re just part of the visual theme and not functional components. To make the experience even more immersive, several vehicles featured displays that were really only visible when looking through the FPV gear, such as digital readouts of the system’s battery voltage.

As impressive as the vehicles of Wasteworld Toys was, it was perhaps Brett himself who left the biggest impression on me. Humble, affable, and eager to share the intricate details of his work, he was even willing to hand the controls of his creations over to attendees, much to their delight. The Wasteworld couldn’t have asked for a better ambassador.

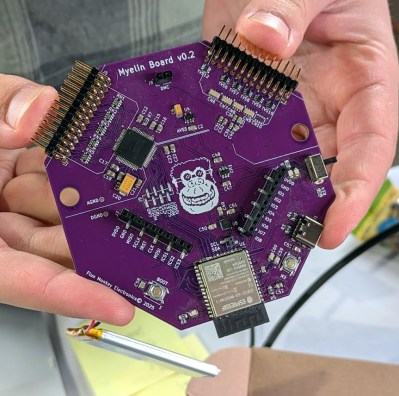

Myelin BCI Board

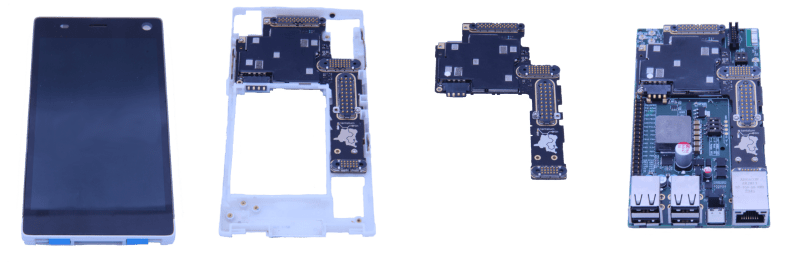

Hackaday readers may recall the OpenBCI project, which made some headlines about a decade ago with their relatively low-cost development boards for experimenting with brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). We covered a few projects that used their software and hardware, including a flying shark controlled by EEG signals.

Hackaday readers may recall the OpenBCI project, which made some headlines about a decade ago with their relatively low-cost development boards for experimenting with brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). We covered a few projects that used their software and hardware, including a flying shark controlled by EEG signals.

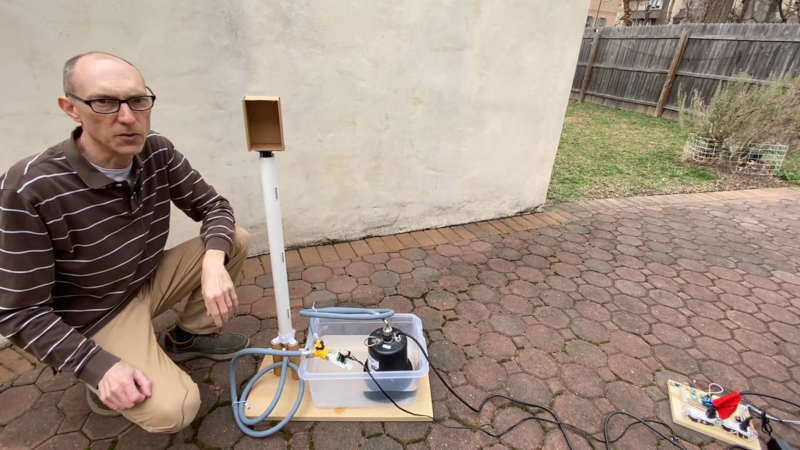

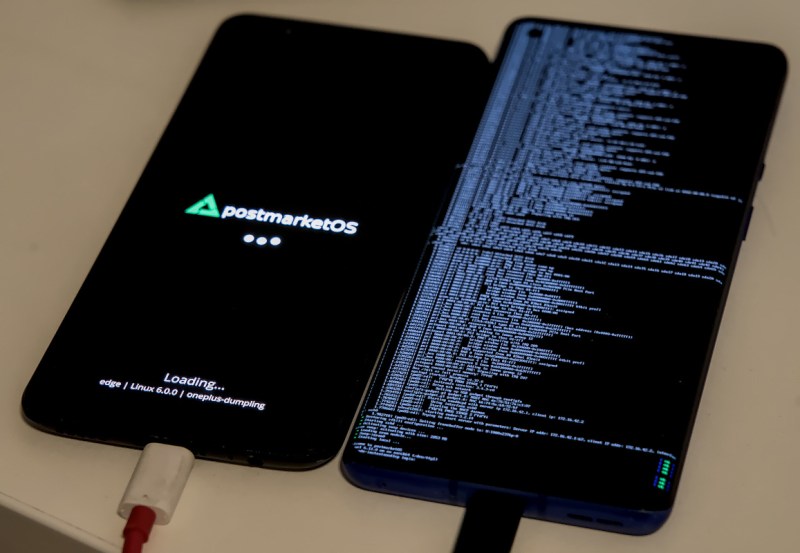

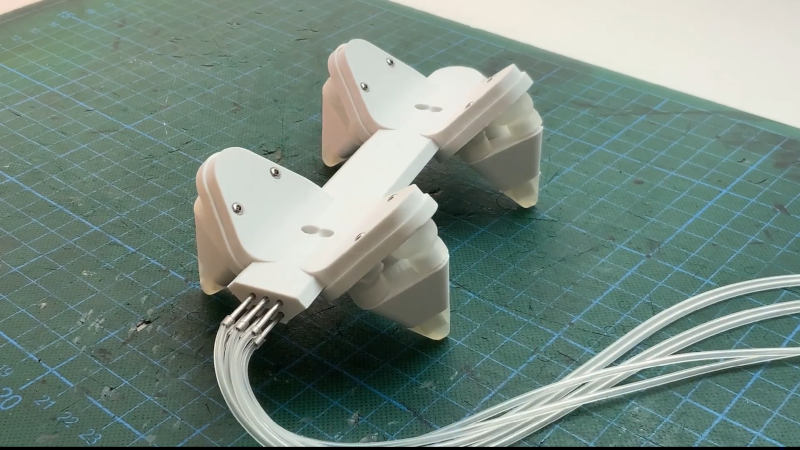

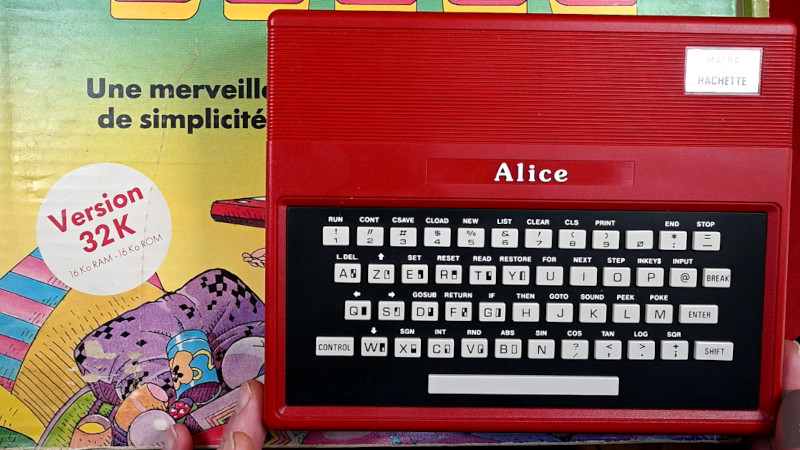

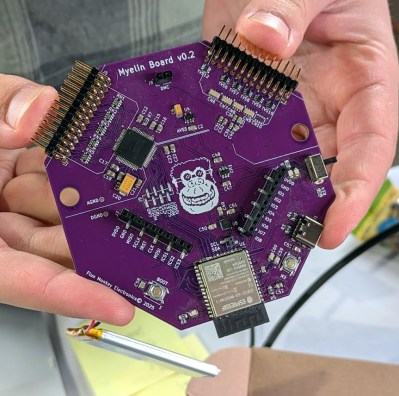

It turns out that OpenBCI has now turned their attention to some kind of mixed reality headset that costs as much as a new car, leaving the future of their more hobbyist friendly hardware in question. Which is why Mike Recine has been working on the Myelin, an open source hardware project that continues the legacy of OpenBCI’s early work. Powered by the ESP32, the battery-powered board can wirelessly link to your phone or computer to deliver 16 channels of EEG data.

Mike is hoping to launch a Kickstarter for the hardware soon, offering up assembled and ready-to-use Myelin boards. Kits are also on the horizon, and of course as an open source hardware project, spinning up your own board will be an option as well. The project doesn’t have much of an online presence currently, but interested parties can sign up to be notified when more information goes live.

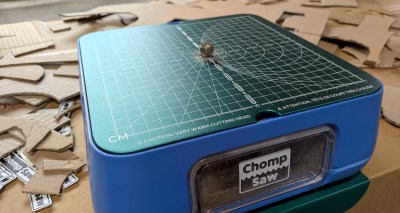

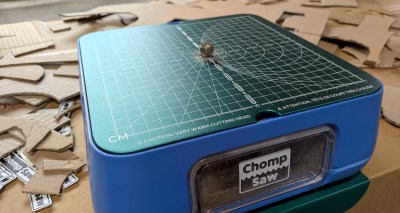

A Cardboard Table Saw

The ChompSaw is advertised as a “kid-safe power tool for cutting cardboard” but it doesn’t take long to realize that’s selling the machine a bit short. There’s no blade in the machine, instead it uses a small metal piston to rapidly nibble away at the cardboard, a mechanism that co-founder Max Liechty says could be thought of as a “full-auto hole punch.” Even though there’s no blade, the business end of the ChompSaw is still under a protective cover that keeps anything thicker than 3 mm cardboard out. You couldn’t hurt yourself with this machine if you tried.

It rapidly rips through cardboard in any direction, making it easy to follow patterns and cut out complex shapes. Though it was designed primarily for common cardboard (think: all those Amazon boxes you’ve got stacked up), it can chew through other thin materials such as paper, foam, and plastic, opening up even more possibilities.

https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/pmf25_chomp.mp4

The ChompSaw brought in over $1 million during its 2023 Kickstarter campaign, and is available for purchase through their site. While it might not seem like the kind of machine we’d usually get excited about at Hackaday, its ability to cut through foam and other materials holds promise for more practical applications than rainy day arts and crafts. Plus, one should never underestimate the value of CAD: Cardboard Aided Design.

The Sights of Philly Maker Faire

[Content truncated due to length...]

From Blog – Hackaday via this RSS feed