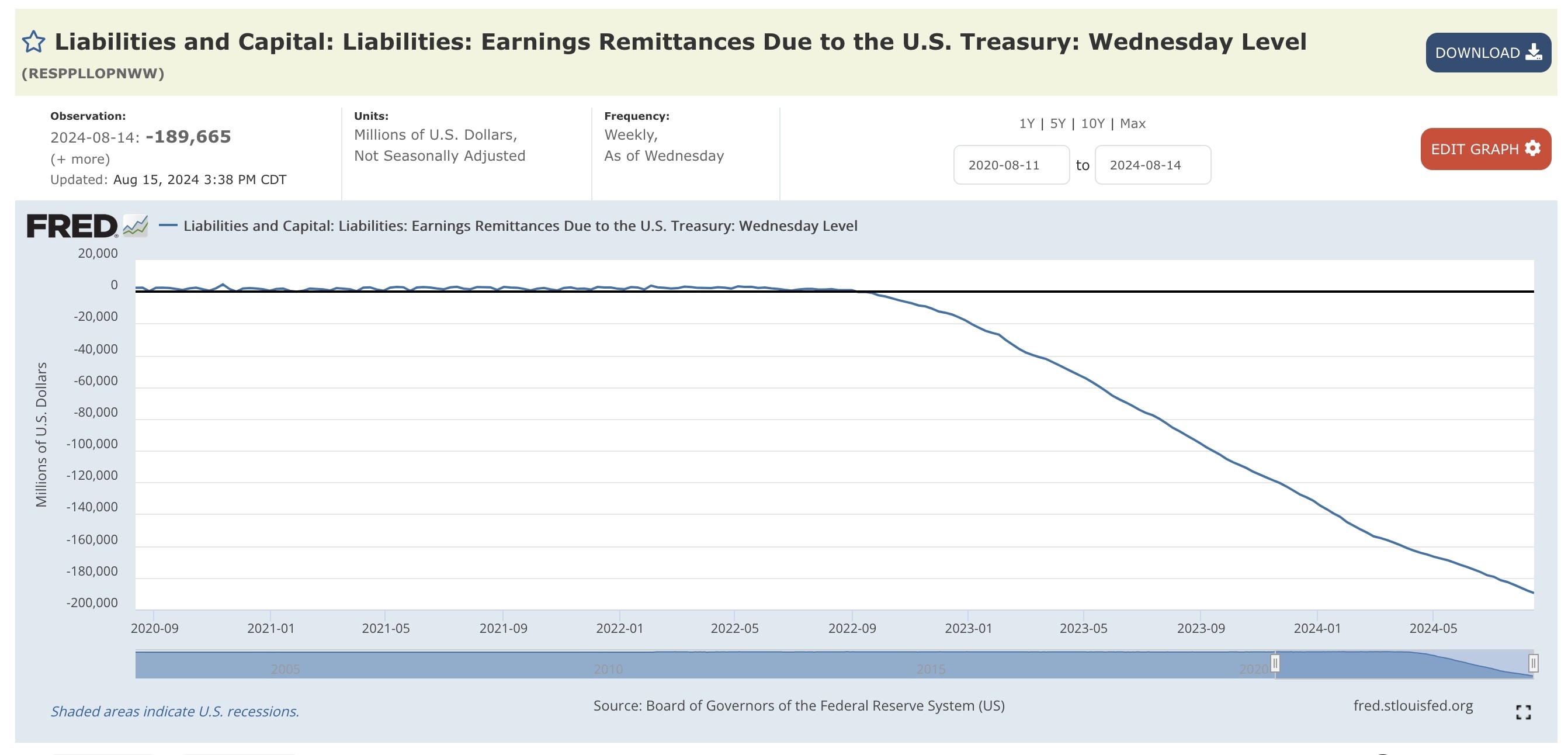

A bit longer explanation of the graph. The US Treasury is effectively the owner of the Federal Reserve’s entire balance sheet. Any profit or loss resulting from the Fed’s monetary policy actions flows back to the Treasury.

For a long time, the Fed’s income from holding Treasury debt and fees from financial institutions outweighed its expenses (like interest paid on reserves and operational costs).

However, when the Fed raised interest rates on reserves from near 0% to around 5% in 2021-2022, its expenses surged. This was because the Fed had trillions of dollars in reserve liabilities after years of Quantitative Easing (QE) – buying Treasury bonds and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) to stimulate the economy.

Reserves are liabilities with variable interest rates, so the Fed’s expenses rose immediately. Meanwhile, its assets (mainly Treasury securities and MBS) pay fixed interest, so their income didn’t increase.

Here’s the problem: the value of the Fed’s assets fell when it raised interest rates. This normally wouldn’t be a major issue, as the Fed could just hold those assets until maturity and receive their full value. However, the Fed has been shrinking its balance sheet via Quantitative Tightening (QT) - selling these securities back into the market at a loss.

The overall impact is that the non-government sector now has more claims on the government than before. Essentially, the government spent money into the economy, exchanged that spending for Treasury bonds, the Fed bought those bonds, and is now selling them back at a loss

The key takeaway is that the Fed’s decisions to raise interest rates and conduct QT have increased the government’s overall interest expenses. This leaves less room for non-inflationary public spending on vital areas like healthcare, education, infrastructure, and so on.