What are the goalposts, so we all have the same frame of reference?

I think the point is that it's a lot easier to "accidentally" hit someone with a car

Steins;Gate and its sequel movie Steins;Gate: The Movie − Load Region of Déjà Vu

It's important to know that both the FDA and the USDA are in charge of inspecting food, and which food is covered by which agency can be complicated.

FSIS [under the USDA] conducts continuous daily inspections of foods in its domain, whereas FDA inspections have no regular schedule. The FDA is more likely to inspect only after a tip about a possible food safety violation, so random inspections can occur up to 10 years apart or, in rare cases, not at all.

“It’s not that they don’t want to inspect more, they just don’t have the funding,” Raymond says.

This inspection imbalance means that pepperoni pizza, because it contains meat, has ingredients that will be inspected three times before the product hits the grocery store freezer: at the slaughterhouse, the packing plant and the pizza factory. A vegetarian pizza produced at the same facility, however, will probably not undergo any inspection.

And in regard to the FDA being not allowed to regulate:

[The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994] placed the burden of proof concerning dietary supplement safety on FDA, requiring the agency to show that a dietary supplement ingredient is adulterated rather than requiring the manufacturer to prove a supplement is safe prior to marketing. This is in contrast to new food additives, which require submission of safety information in a food additive petition prior to marketing, or drugs, which generally require submission of safety data as part of a new drug application prior to marketing.

At least with dietary supplements, they can't make a new product guarantee it's safe, the FDA needs to already know something is dangerous before it can force a recall.

If you'd prefer to learn more through a comedian, John Oliver covered this topic a while back https://youtu.be/Za45bT41sXg

You're definitely wrong about India, and famously China Added More Solar Panels in 2023 Than US Did In Its Entire History, so I don't see why we can't be trying to reduce emissions too.

Then go away and live your life. Let the people who are angry and energized yell at companies to try and get better conditions for consumers.

Another big example is any web-browser that isn't safari. That should be changing soon/recently (see here https://www.theverge.com/2024/1/25/24050478/apple-ios-17-4-browser-engines-eu) but that's only because Apple was forced to.

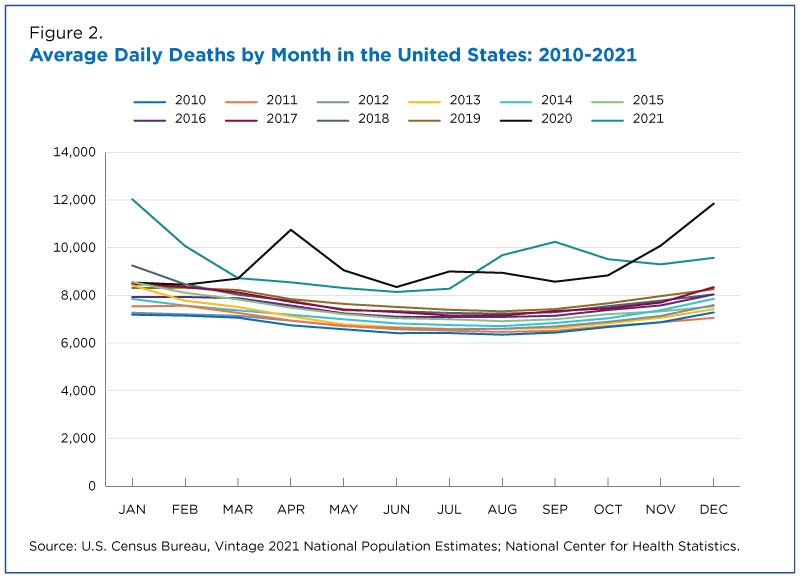

You should probably be looking at trends over a longer period of time, rather than just a single month.

From here. There was a dip below the 2016-2019 average in January through March of 2023, but time marches on.

The numbers for 2023 are no higher than normal either

The numbers for 2023 in the 2-3 months you have data for. Look at the rest of the graph, how it starts off lower in January and is higher for the rest of the year. Go back up and look at this graph

and see how covid comes in waves each year, not evenly distributed throughout. Then go back and look at this graph

and see that based on the data we have in the US, deaths per year has stayed above the previous yearly patterns. We don't have all the data over a long period of time because covid hasn't been around for all that long. But from what we can see so far, it kills people. The exact number per year remains to be seen, but from the data we have it's been in the thousands, just in Norway.

Edit: I guess next time I see a fucking “mOVInG tHe GOOalPoSt!!!” I will take the clue and not fucking bother.

Half of the sources you posted actively worked against your own arguments. Maybe you shouldn't bother.

EDIT of my own: After looking at one of your sources (Eurostat)

you can see that January-March was lower than 2016-2019, but it's been on the rise again across the EU, and especially in Norway. Again, you can't just look at one single month and decide that it's representative of everything, everywhere, across all time going forward.

Harry’s whole life and the plot.

Oh, well you see, the bad things that happen to Harry are depicted as bad by the book, whereas the slavery of the house elves is depicted as a good thing, or at least how things should be. The characters don't just shrug off someone's death and say "they'd be happy to have died for the cause," but they do say "house elves are happy to work, so we shouldn't end their slavery." That's the problematic part, and what makes it worse and worth talking about.

No, you see that because it’s what you want to see. She’s nuts but not pro slavery, and I think thats obvious to most readers.

She's very pro- house elf slavery. I don't know how you're reading the book (or just the wiki page in this case) and coming to another conclusion. The person trying to free them is seen as ridiculous, every character besides her thinks she's a hopeless idealist who doesn't know how the world works for wanting to end slavery, and even the main character sides more with the "why is she so upset about this" side than "we should end slavery".

I don't know how long that video actually is, but a lot of it is made up of unrelated clips of lions and tigers not even in the same location with a couple of clips of lions and tigers "fighting" for less than a minute before they both back off.