335

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

this post was submitted on 31 Dec 2025

335 points (99.1% liked)

Climate - truthful information about climate, related activism and politics.

7738 readers

559 users here now

Discussion of climate, how it is changing, activism around that, the politics, and the energy systems change we need in order to stabilize things.

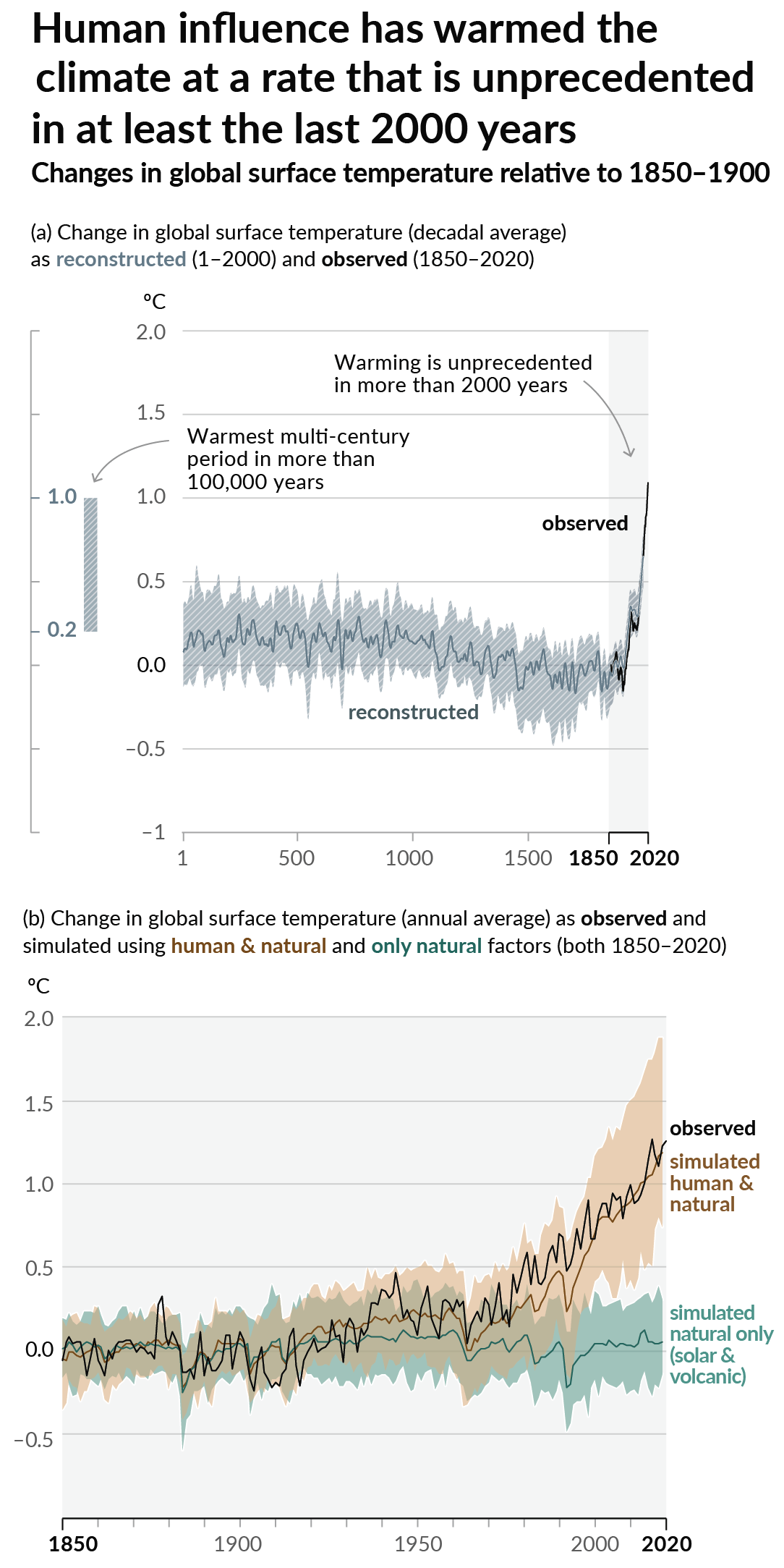

As a starting point, the burning of fossil fuels, and to a lesser extent deforestation and release of methane are responsible for the warming in recent decades:

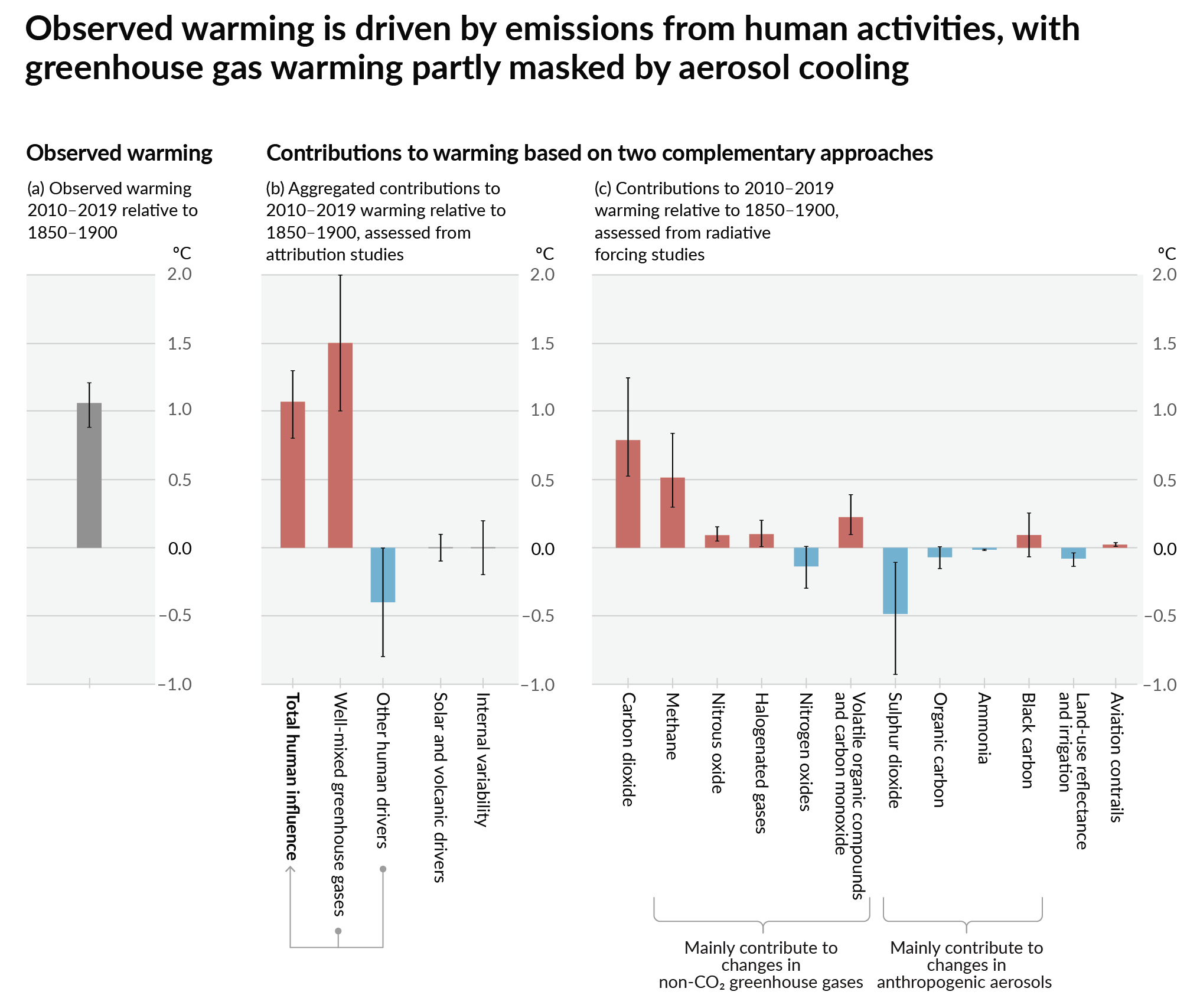

How much each change to the atmosphere has warmed the world:

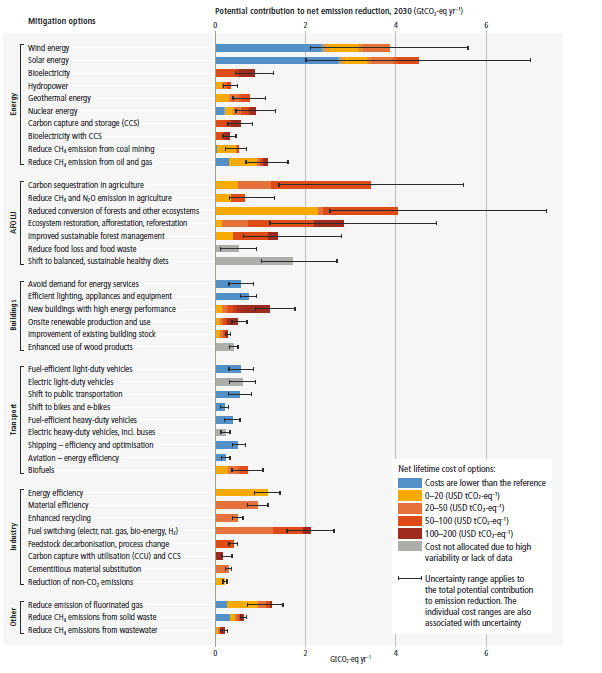

Recommended actions to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the near future:

Anti-science, inactivism, and unsupported conspiracy theories are not ok here.

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

I've removed this post due to misinformation. Copper and aluminum pots on an induction stove arent forbidden; they just don't get hot on an induction stove.

Thanks for correcting.

There seems to be contradictory information on the subject.

Aluminum foil is proven to melt on induction cookers (see attached photo). But that's because foil is thin.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Foil_on_induction_cooktop.jpg

A photo I suggest taking a look at: induction heater burning aluminum foil. Taken from the publication "Practical Course on School Experiments for Future Physics teachers".

...as for thick aluminum cookware, or copper cookware, I was not implying that they would overheat themselves, I was implying that the induction cooker would overheat its coil attempting to work with them, because they conduct current better than the coil. But perhaps that's prevented by protection circuits or a process I haven't taken into account. I can't test since I don't have an induction cooker at home.

EM-fields induce current in copper and aluminum perfectly fine, no ferromagnetism is needed. You can build a coreless transformer for example, ordinary tranformers simply benefit from having a core (the core is separated into thin layers to reduce heating). Copper and aluminum simply conduct current very well, so appreciable heat does not appear at everyday levels of field strength and current. Steel and cast iron, having considerable resistance, heat up in a similar field, conducting similar amounts of current. There's a potential gap in my understanding of the process, however - perhaps I'm failing to take into account the frequency of a cooking field in an induction cooker. The frequency determines whether current wants to travel in the depth of the conductor or on the surface of the conductor.

Simple experiments that I can recommend:

take a circuar magnet and let it drop along a copper pipe -> you will observe that it drops slowly, braking itself by inducing current in copper

spin a rotor with magnets next to a plate of copper -> you will observe mechanical resistance to spinning, because it induces current in copper

I can also recommend an interesting Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eddy_current

Quoting from the article (emphasis mine):

I also recommend this source and will quote them below:

This stuff would matter if induction stoves just had a raw component and no cooling or temperatue sensor or pot presence sensor. They're an engineered product which doesn't fail in the same way that the raw components do without any of that.