Physician and proponent of the Canadian abortion rights movement. Born in Lodz, Poland, on March 19, 1923, he died on May 29, 2013, in Toronto, Canada, aged 90 years.

He was acclaimed as a Canadian hero, a champion of the women's rights movement, and in 2008 awarded the Order of Canada, one of the nation's highest honours. Yet when Henry Morgentaler died there were few words of praise from the country's ruling elite and the location of his funeral was kept a secret for fear it would draw anti-abortion protesters. Even in death Morgentaler, the man who did more than any other to change Canada's restrictive abortion law, was a divisive figure.

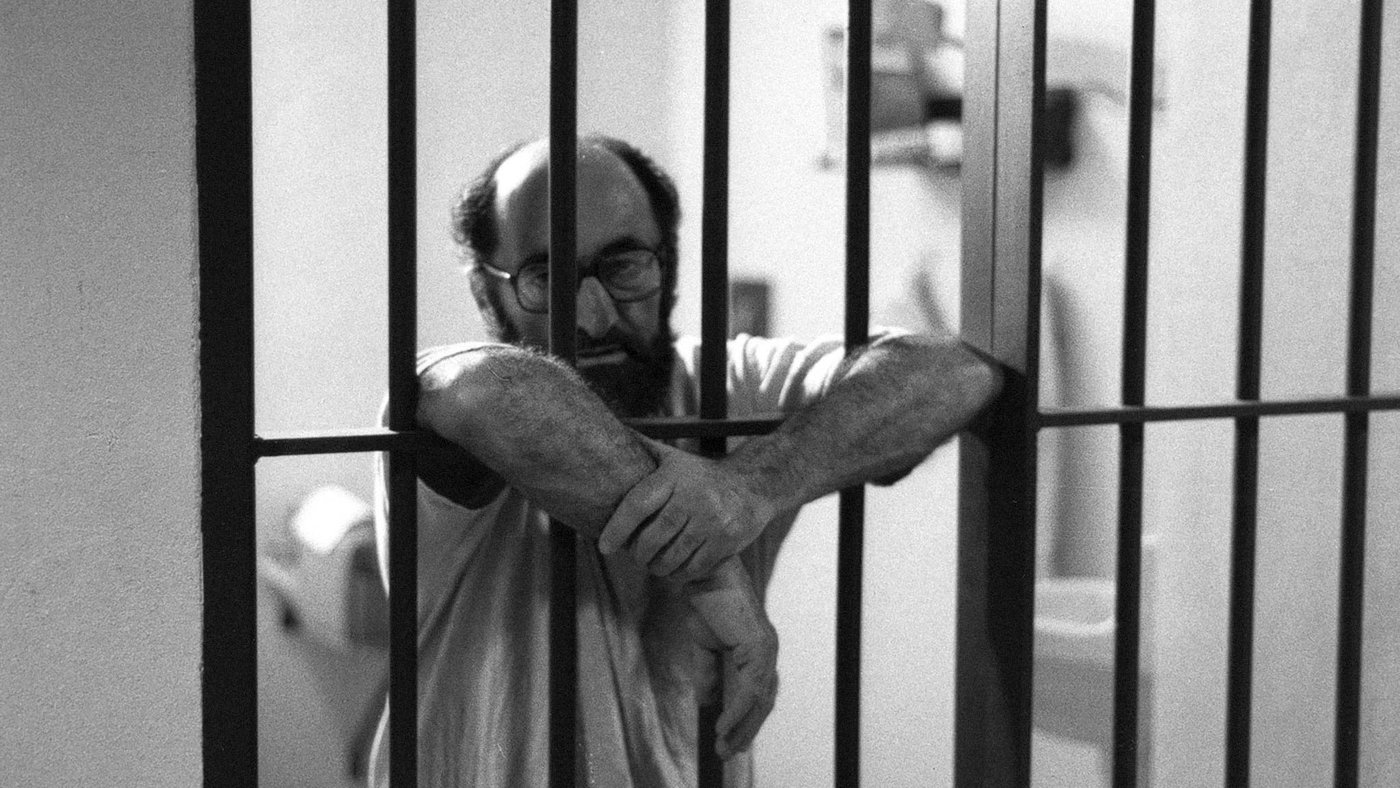

Morgentaler did his first abortion in 1968—on the 18-year-old daughter of a friend—when the deed was punishable by life imprisonment. “I decided to break the law to provide a necessary medical service because women were dying at the hands of butchers and incompetent quacks, and there was no one there to help them. The law was barbarous, cruel and unjust”, he said. Over the next two decades Morgentaler opened a chain of clinics across Canada, trained scores of doctors, and performed thousands more terminations himself. He was assaulted and imprisoned, attacked, one clinic was firebombed, and he took to wearing a bulletproof vest. But in 1988 he won a historic victory when the Supreme Court of Canada removed all legal restrictions on abortion, which led to the spread of abortion clinics nationwide.

A Holocaust survivor, Morgentaler said his imprisonment by the Nazis in the Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps honed his sense of injustice and prepared him for the battles ahead. But he caused anger and frustration among some of his supporters with his imperious and authoritarian style. “He was not a team player”, said Catherine Dunphy, author of the book Morgentaler: A Difficult Hero. Yet his supporters said that without him, they would never have achieved what they did.

The son of Jewish socialists, Morgentaler spent much of World War 2 in Poland's Lodz ghetto with his mother, brother, and sister. His sister died there. His father, a textile worker and union organiser, had been killed by the Gestapo when the Nazis invaded in 1939. He was sent to Auschwitz with his mother and brother in 1944 where his mother was executed. After liberation in 1945 he studied medicine in Germany and Belgium before moving to Canada in 1950, where he completed his medical training at the University of Montreal. He settled down as a general practitioner in a working-class district of the city where he remained for the next 15 years. He had married his childhood sweetheart, Chava Rosenfarb, in 1949, and they had two children.

But Morgentaler was not satisfied with a quiet life; he joined humanist groups and in 1967 addressed a parliamentary group calling for safe, unrestricted abortion. That changed everything. Afterwards he was swamped with requests for terminations which he initially refused until his feelings of cowardice and hypocrisy overcame him. By then he was already in his mid-40s and for the next 20 years he battled the Canadian authorities and was rarely out of the headlines. Judy Rebick, the feminist campaigner and author who became spokesperson for his Toronto clinic from its opening in 1982, said he had not looked for the cause—it had found him. “He was challenged by women who wanted help. It was pretty rare for someone in their 50s to confront the law and risk everything. Especially a doctor living a comfortable life. His willingness to risk everything inspired a lot of people”, Rebick said.

Morgentaler himself believed abortion would reduce crime. “Well-loved children grow into adults who do not build concentration camps, do notremoved and do not murder”, he said in 2005, on being awarded an honorary degree by the University of Western Ontario. The award cost the university a bequest of CAN$2 million, withdrawn as a result. Despite being a diminutive figure, Morgentaler had an imposing, charismatic personality. After divorcing Chava Rosenfarb he married Carmen Wernli in 1979, by whom he had a son before a second divorce. Later he married Arlene Leibovich and had another son. She and his four children survive him. A few months before his death a group of friends and supporters gathered at his Toronto home to mark the 25th anniversary of the Supreme Court's decision. Christopher DiCarlo, a family friend who spoke at the celebration, said: “Henry stood his ground and succeeded where so many refused to go.”

Well it was a nice article until the first sentence of the last paragraph. But I am deciding to keep this piece in the interest of honesty.

:

:

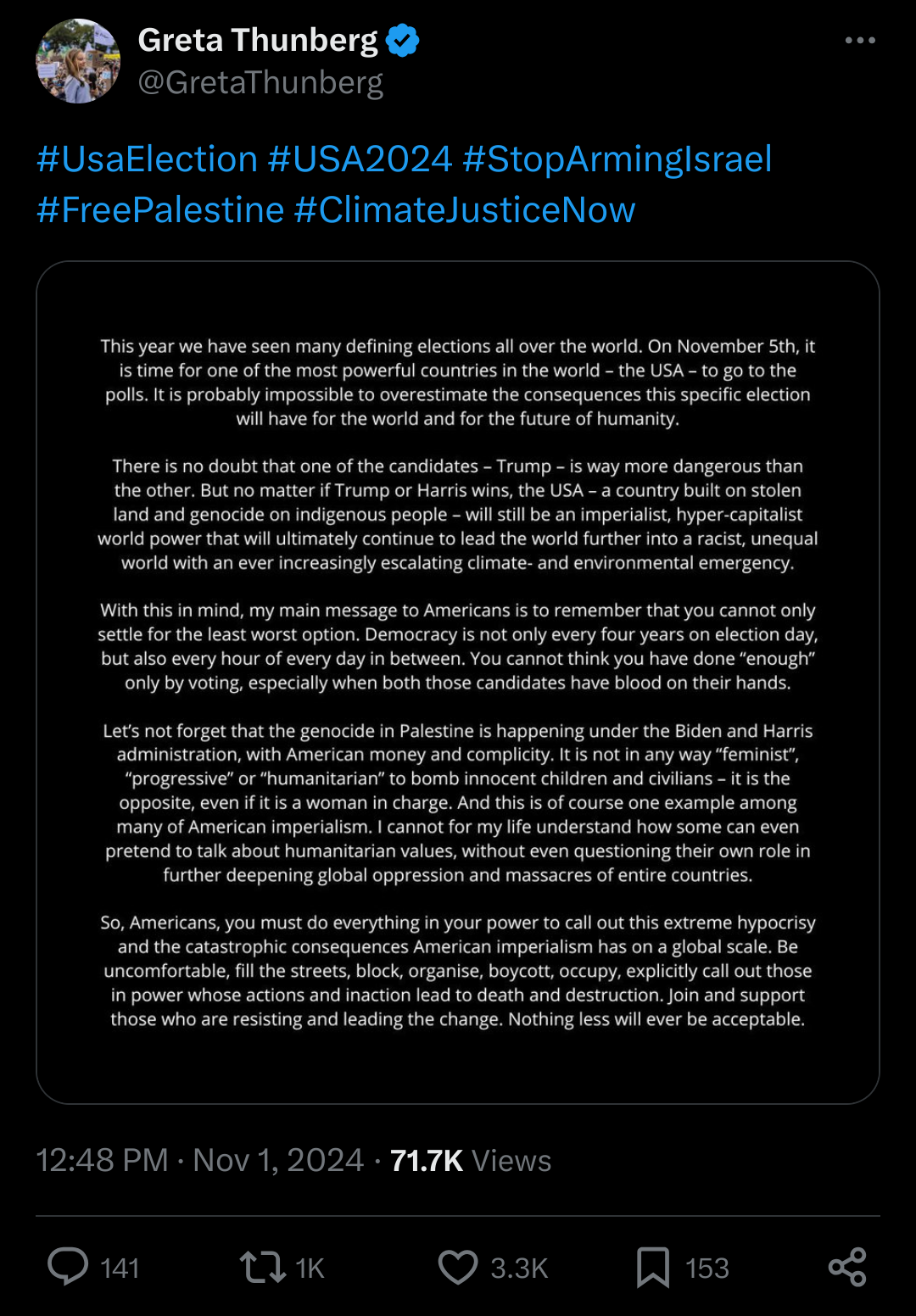

because I clearly am privileged and don't understand how much the marginalized need the godsent revolutionary leader, Kamala Harris, who will purge society of all reactionary and bourgeois tendencies and definitely not further those tendencies instead.

because I clearly am privileged and don't understand how much the marginalized need the godsent revolutionary leader, Kamala Harris, who will purge society of all reactionary and bourgeois tendencies and definitely not further those tendencies instead.